The new Codes of Conduct for Nurses and Midwives in Australia have made the news. The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) have set expectations around culturally safe practice in the health system for nurses and midwives who comprise the largest workforce in healthcare.The incorporation of cultural safety into nursing in Australia has support from The Council of Deans of Nursing and Midwifery:

The Council of Deans of Nursing and Midwifery ANZ acknowledge Aboriginal & Torres Strait

Islander people as the First Nations people of Australia. The Council supports the

development and implementation of cultural safety in education programs, practice, and

research activities for nurses and midwives. It also recognises that the origins and context

informing the development of cultural safety arise from different historical, political, economic

social and ideological positions in Australia and New Zealand and therefore this will be

acknowledged separately

However, this explicitly anti-racist and equity informed strategy has not gone down well with The Nurses Professional Association of Queensland Inc (NPAQ). Run by union-buster Graeme Haycroft who calls the Codes ‘racist’, the association brands itself as a non party political alternative to existing unions. Haycroft has garnered a deluge of support (despite not being political) and claims NPAQ members were not consulted and 50 per cent of NPAQ members are opposed to the Codes. Interviewed by Sky News host Peta Credlin, supporters like Andrew Bolt have jumped into the fray with headlines screaming: Nurses forced to announce ‘white privilege’ is new racism. The hyperbole has been astounding:

What if… they’re within seconds of dying and the nurse has to fling themselves into action but they have to stop while they just announce their white privilege?

A clear early rebuttal came from The Queensland Nurses and Midwives’ Union (QNMU) Secretary Beth Mohle when Cory Bernardi first expressed indignation:

These codes were the subject of lengthy consultations with the professions of nursing and midwifery and other stakeholders including community representatives. This review was comprehensive and evidenced-based. Our union and our national body the Australian Nursing Midwifery Federation (ANMF) were active participants in these consultations.

The codes, written by nurses and midwives for nurses and midwives, seek to ensure the individual needs and backgrounds of each patient are taken into account during treatment.

There’s no doubt cultural factors, including how a patient feels while within the health system, can impact wellbeing. For example, culture and background often determine how a patient would prefer to give birth or pass away.

Every day, nurses and midwives consider a range of complex factors, including a patient’s background and culture to determine the best treatment. These codes simply articulate what is required to support safe nursing and midwifery practice for all.

Further rebuttals have entered the public sphere, including a joint statement from Nursing organisations including the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia; Australian College of Midwives (ACM); Australian College of Nursing (ACN); Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives and A/Federal Secretary Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation which have also been supported by the Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association, Public Health Association of Australia, Consumers Health Forum of Australia and National Rural Health Alliance. As CEO of CATSINaM Janine Mohamed observes in a blog for Indigenous X “Australia is playing a game of ‘catch up’”. Indeed, cultural safety is an approach developed by indigenous Māori nurses that is embedded in the undergraduate national nursing curriculum, and broadly applied across marginalised groups in New Zealand. The Nursing Council of New Zealand introduced the concept into nursing and midwifery curricula in 1992, developing the expectation that nurses practise in a ‘culturally safe’ manner. It wasn’t without resistance, however. As a nurse, academic and researcher, cultural safety has informed my professional practice. I completed a PhD which attempted to extend the theory and practice of cultural safety to both critique nursing’s Anglo-European knowledge base, and to extend the discipline’s intellectual and political mandate with the aim of providing effective support to diverse groups of mothers (Migrant Maternity).

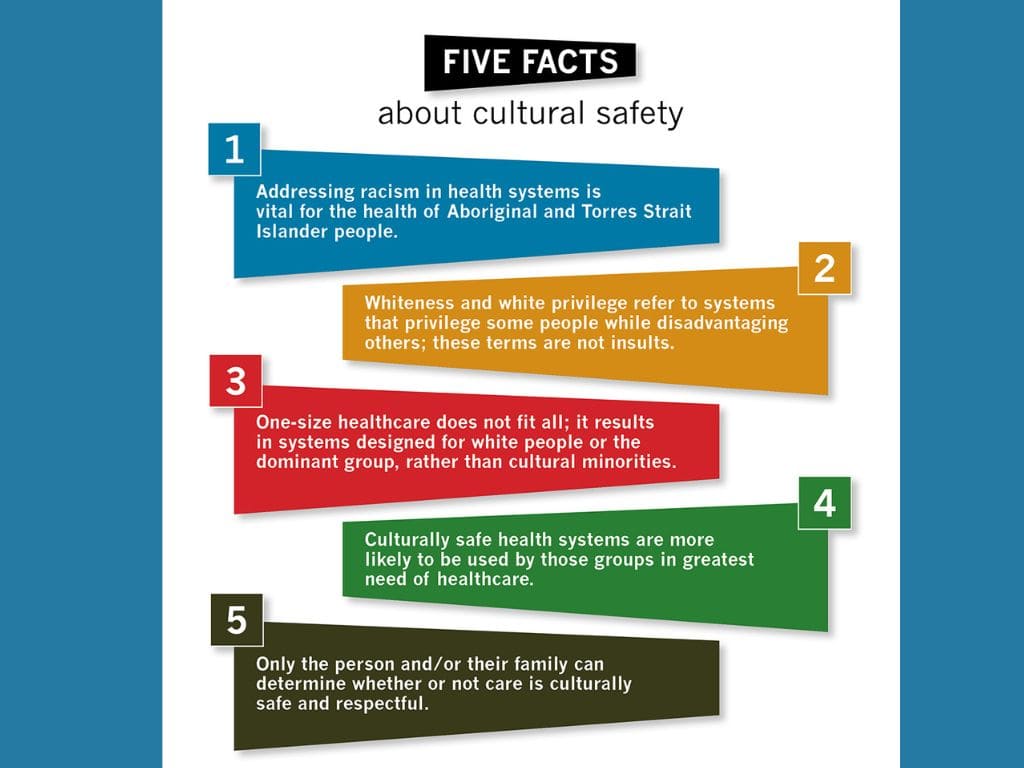

I am pleased to contribute to the conversation about cultural safety and nursing. I wrote this piece called Busting five myths about cultural safety – please take note, Sky News et al for Croakey. My appreciation to Melissa Sweet and Mitchell Ward from Rock Lily Design for the terrific infographic.

Myth 1

Cultural safety is creating racism, not eliminating it. It’s political correctness gone mad!

Correction: Race is a proven determinant of health. The Nursing and Midwifery Codes of Conduct acknowledge racism and attempt to reduce its impact on health.

Australia is a white settler society like the United States, Canada and New Zealand. In such settler societies, colonisation and racism have had devastating effects on Indigenous health and wellbeing. These include: the theft of land and economic resources; the deliberate marginalisation and erasure of cultural beliefs, practices and language; and the forced imposition of British models of health over systems of healing that had been in Australia for millennia.

Along with the systematic destruction of these basic tools for wellbeing, interpersonal racism has also contributed to a reduction in access to health promoting resources for Indigenous communities. Cultural safety was developed and led by Indigenous nurses in New Zealand to mitigate the harms of colonisation and improve health care quality and outcomes for Māori, and this has been extended by nurses in Australia, Canada and the US.

Evidence demonstrates that health system adaptations informed by a cultural safety approach have benefits for the broader community. For example, in New Zealand, the request by Māori to have family involved in care (whānau support) have led to a more family-oriented health care system for everyone.

Myth 2

I’m white but I’ve had a hard life, who is to say that I am privileged? Why am I being called racist for being white? That’s racist! I am a nurse, I’ve been abused, I am not privileged. I fought hard for everything I have and have achieved today.

Correction: Whiteness and white privilege refers to a system, they are not an insult.

Scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson points out that British invasion and colonisation institutionalised whiteness into every aspect of law and policy in Australia. One of the first actions of the newly formed Australian nation state in 1901 was to pass the Immigration Restriction Act restricting the entry of non-white people.

The White Australia policy ended in 1962, when some of our lawmakers today were adults. Unsurprisingly, politicians have reflected these assumptions as they have demonised successive groups of migrants and refugees.

This culture of whiteness confers dominance and privilege to those who are located as white, but is largely invisible to them, and very visible to those who are not white. Being white in a settler colony like Australia means that you can move through daily life in a world that has been designed by people who are white for people who are white.

Even accounting for class and poverty, people who are white experience privileges that are not available to people of colour. White people can’t actually be systematically oppressed on the basis of their race by Indigenous people or people of colour, because the colonial systems of governance are still in force.

As the comedian Aamer Rahman points out, so called “reverse racism” would only exist under circumstances where white people had been intergenerationally marginalised from the social and economic resources of the nation on the basis of their race. The way Graeme Haycroft from the Nurses Professional Association of Queensland Inc attempts to create equivalence between the inconvenience of having to think differently about health with generations of dispossession is farcical and insulting.

Myth 3

Why can’t we treat everyone with respect? Dividing people into categories of oppressors and victims isn’t helpful. I respect each patient and their diversity as I respect all the nurses I work with and their cultural diversity.

Correction: No matter what individuals believe, entering the health system is not always a safe experience for cultural minorities. Providing tailored care where possible helps the health system work for everyone.

One size does not fit all. It’s not helpful to treat everybody the same or to say that one does not see colour. How one shows respect varies from one person to the next. Some things work for some people, while others don’t.

Many nurses and midwives already tailor health care to people’s bodies, genders, class and sexuality. For example, the grumpy old entitled man is a well-known “type” of patient that nurses have dealt with for generations, disrupting their own routines and responding to patient demands in order to get them to accept the care required.

Cultural safety promotes an understanding of the culture of health and asks nurses and midwives to be learn to be more responsive to the needs of the patient generally, and this only benefits patients.

Cultural safety asks caregivers to challenge biases and implicit assumptions in order to improve healthcare experiences for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In the codes, cultural safety also applies to any person or group of people who may differ from the nurse/midwife due to race, disability, socioeconomic status, age, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, migrant/refugee status, religious belief or political beliefs.

In other words, where “business as usual” is designed for white people, cultural safety is for everyone.

Myth 4

Why is cultural safety being regarded in the new Codes of Conduct as equally important to the patient as clinical safety? Doesn’t that devalue clinical care?

Correction: Cultural safety enhances clinical safety.

People are more likely to use health services that are appropriate, accessible and acceptable. If people don’t use health services because they do not trust them or find them unsafe, then they are more likely to become very ill or die unnecessarily.

The health system is not accessed equally by all Australians who need it. For example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people access health services at less than half of their expected need. Safety and quality of care are also linked with culture and language. Research shows that people from minority cultural and language backgrounds are more at risk of experiencing preventable adverse events compared to white patients.

In Australia lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI) people often receive inappropriate medical care, and experience health inequities compared to the general population around drug and alcohol use; sexual health and mental health issues.

Discrimination, transphobia, homophobia and a lack of cultural safety from health professionals discourage help seeking. Having services that are welcoming and safe would facilitate equitable health outcomes for all these groups.

Myth 5

There is no objective assessment of what constitutes “cultural safety”.

Correction: Only the person and/or their family can determine whether or not care is culturally safe and respectful.

The most transformative aspect of cultural safety is a patient centered care approach, which emphasises sharing decision-making, information, power and responsibility. It asks us as clinicians to demonstrate respect for the values and beliefs of the patient and their family; advocating for flexibility in health care delivery and moving beyond paternalistic models of care.

Patient-centred care is institutionalised in the Australian Charter of Health Care Rights (ACSQHC, 2007) and the Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Service Standards (2017) Partnering with consumers (Standard 2).

Cultural safety challenges nurses and midwives to work in partnership with people and communities but acknowledges that the system is weighted towards the interests of those who work in the system. We think we give the same care to everyone, but everyone experiences our care differently.

Once we understand ourselves and our health system as having a culture that privileges some people over others – whether we are conscious of it or not – we can get on with the real work of implementing better healthcare experiences for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and other marginalised groups.