I’m interested in what moves us from being bystanders and witnesses to injustice to being moved to act. This has been prompted by several incidents since I arrived in Australia and a few days ago, the savage beating to death of a transgender woman of colour. In our increasingly surveilled and fear based society, there seem to be more effective structures and mechanisms for contributing to injustice than remedying it. In many cases our political leadership promulgate fear and distrust in a bid to retain or increase voters, hate which is then fanned and fuelled by the media. Take the invitation to police our neighbours in the form of immigration policy in both the United Kingdom and Australia. The Immigration Dob-in Service on the website of the Australian Government’s Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) being a prime example of how with a few clicks and some information “the community” are encouraged to “dob in” people. Similarly the The UK Home Office had vans warning illegal immigrants to “go home” which demonstrated how easily the government could ignore and breach its responsibilities under the Equalities Act (eliminating discrimination and harassment based on race and religion, fostering good relations between people from different racial and religious groups).

Photograph: Rick Findler

Luckily the racist vans were subverted with civil liberties group Liberty organising an alternative message. Other advocacy groups such as Amnesty, Refugee Action and Freedom from Torture claimed in a letter to the Guardian:

As organisations with expertise in supporting people who are seeking protection in the UK, we deplore the highly controversial advertising campaign delivered on the side of vans driven through selected London boroughs

The ‘illegal immigrants go home campaign’ is cynical and giving rise to a climate of fear. The heavy-handed ‘stop and search’ activity outside London tube stations harks back to a period before the Lawrence inquiry and raises questions about racial profiling in immigration control

But what if you are an individual who would like to respond to racism but feel overwhelmed and powerless? A recent study by VicHealth (with the University of Melbourne and the Social Research Centre) investigated the role of bystanders and racist incidents by sampling 601 Victorians and asking them whether racism was acceptable in various scenarios in social settings, workplaces and sports clubs; what they would do if they witnessed racism in these scenarios and what they did the last time they witnessed a racist incident. You might have heard about the many incidents of racist violence and abuse on public transport and in sport.

The purpose of the study was to consider whether reducing racist incidents or the impact of incidents could prevent distress and illnesses in Victorian people from Aboriginal and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. People from Aboriginal and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds experience the highest volumes of racism and record the most severe psychological distress, which places them at higher risk than others of mental illnesses (Ferdinand, Paradies & Kelaher, 2013a; 2013b). The VicHealth study found that individuals’ coping strategies provided insufficient protection from harm, and therefore broader community and organisational efforts were needed to stop racism from occurring and that the role of bystanders was a particularly important one.

Encouragingly the study found that 83% of participants felt that more could be done to address race-based discrimination in settings such as workplaces and sporting clubs such as education, promoting cultures of respect and taking action when racist incidents occurred. 84% claimed they would take action against racism with 30 per cent willing to act on every occasion. However, 13 per cent to 34 per cent (approximately one in four people across the sample) claimed they would feel uncomfortable if they witnessed racism, but would not do anything. I agree with the authors that this group of people hold the potential for a new, powerful wave of action. Take this lovely example of an intervention in a supermarket from Upworthy: One Easy Thing All White People Could Do That Would Make The World A Better Place.

That action was a powerful one, but not all bystanders would be willing to act. Imagine though if all bystanders could be moved to act in small ways in their own workplace or social setting and their efforts were co-ordinated. That’s one of the reasons I love the New Zealand Diversity Action Programme, facilitated by the Human Rights Commission who hold their annual forum this week. The programme brings together organisations taking practical initiatives to:

recognise and celebrate the cultural diversity of our society (diverse) promote the equal enjoyment by everyone of their civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, regardless of race, colour, religion, ethnicity or national origin (equal)foster harmonious relations between diverse peoples (harmonious)fulfill the promise of the Treaty of Waitangi (Treaty-based)

Any organisation that supports the vision of an Aotearoa New Zealand that is “culturally diverse, equal and harmonious” can take part. All they need to do is to commit on an annual basis to taking practical steps to making this vision happen and these steps can be big, small or celebratory.

In the spirit of the Diversity Action Programme, this story about Mariam Issa a former refugee is delightful. Mariam transformed her backyard into a public garden, complete with chooks. She runs regular storytelling sessions bringing women from her middle-class suburb together with former refugees to share stories and better understand each other. Her story inspired me to think how food and conversations might also help us to to shift from bystander to ally and address unequal power relations and racism. I wonder if her new middle-class friends have made that transition?

I loved Mariam’s story because it made me think that the domestic worlds of food and garden can be such potent sites of transformation for social justice. I am a committed foodie (“somebody with a strong interest in learning about and eating good food who is not directly employed in the food industry” (Johnston and Baumann, 2010: 61), who is also interested in the politics of food. My partner and I moved to Victoria, Australia this year near Melbourne, a foodie paradise. Melbourne’s food culture has been made vibrant by the waves of migrants who have put pressure on public institutions, to expand and diversify their gastronomic offerings for a wider range of people. However, our consumption can naturalise and make invisible colonial and racialised relations. Thus the violent histories of invasion and starvation by the first white settlers, the convicts whose theft of food had them sent to Australia and absorbed into the cruel colonial project of poisoning, starving and rationing indigenous people remain hidden from view. So although we might love the food we might not care about the cooks at all as Rhoda Roberts points out:

In Australia, food and culinary delights are always accepted before the differences and backgrounds of the origin of the aroma are

Imagining an alternative Australian future, David Liddle asks if instead of clearing the land and its people and replacing them with cattle, the new settlers had eaten with Aboriginal people a new form of co-existence might have come into play. As a newcomer to Australia I am only just beginning to grasp this history and I know I have a lot to learn.

Which brings me to the crux of this post, can the consumption of food move us from being passive consumers, bystanders if you like, to being engaged allies in the face of racism? The example of the Conflict Kitchen, a restaurant in Pittsburgh which prepares food exclusively from countries currently in conflict with the U.S makes me think it’s possible. Highlighted in a piece in Take Part, the idea is that by eating food from such a country, “the enemy” is humanised and the consumer has an opportunity to deepen their appreciation of cultural difference. Not only is a meal provided but insight into political conflicts and world affairs through performances, discussions and stories about that country is part of the whole experience. Their website says:

…Conflict Kitchen uses the social relations of food and economic exchange to engage the general public in discussions about countries, cultures, and people that they might know little about outside of the polarizing rhetoric of governmental politics and the narrow lens of media headlines.

Closer to my new home is the wonderful initiative by the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC), which has a Hot Potato travelling van rolling out across Australia and challenging Australia to 10 million conversations in the lead up to the federal election. The idea is to take the heat out of the asylum seeker conversation and debunk the myths—given that everyone in Australia has an opinion, the ASRC’s aim is to attempt to cool a highly politicised debate with facts. The ASRC claims this Australian political Hot Potato, has been manipulated and passed from one politician to another and heated up by the media.

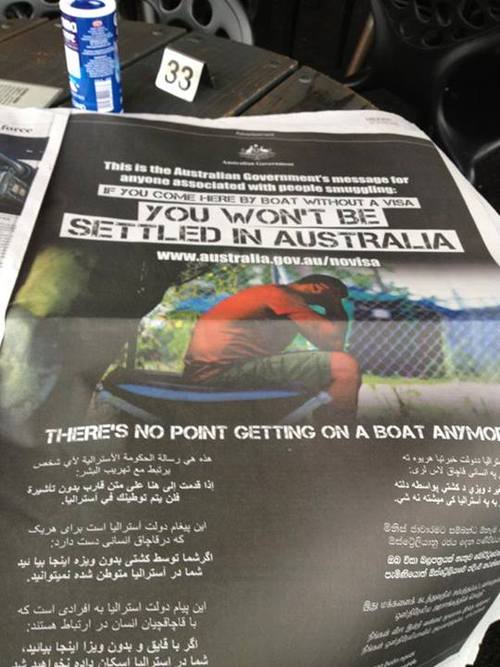

Unless you’ve been sleeping under a rock, you will know that Australia’s Humanitarian Program has made the news for all the wrong reasons, namely it’s harsh treatment of asylum seekers arriving by boat (Irregular Maritime Arrivals). There’s a huge drive to deter people arriving in this way (you can watch the videos on the DIAC webpage called “Don’t be sorry” which features prominent sportsmen). Australia has been roundly criticised for its migration policy of August 2012 which instigated offshore processing of protection (asylum) claims in Nauru and Papua New Guinea.

What I love about the hot potato venture are two things. First of all, food is an expression of generosity and hospitality. So these folk aren’t charging anyone for the food. Secondly, the consumption of the food moves away from the foodie zone which:

operate[s] as a field of distinction, marking boundaries of status through the display of taste … The professional and managerial classes are thronging to ethnic cuisine restaurants, while poor, working class, older, provincial people are not. Familiarity with ethnic cuisine is a mark of refinement. (Warde and Martens 2000: 226)3

So anyone can go and have a conversation with the hot potato van regardless of income.

I’ve always thought that eating food from other cultures offered a bridge to empathy and affection for different people as a starting point, and potentially a non-threatening way of developing an ongoing engagement, even ultimately world peace. I mean imagine if instead of bombing and fighting, we had cook offs? Perhaps if we all do a little something, whether it is food and conversation, we might have a chance of realising a vision of a world without racism.

Going back to the VicHealth study, the characteristics of allies (or as they call them active bystanders) were that they were more likely to recognise race-based discrimination, understand the harm it caused, feel a responsibility to intervene, and feel confident to intervene. They were more likely to act in work or social settings if they were supported by their organisations (via policies, culture etc) peers and colleagues. If we are to do our part to reduce or eliminate the harms of racism it will take all of us.

If you want to know where to start, here are some resources:

- A terrific video of Dr. Omi Osun Joni L. Jones’ keynote speech from September 2010 at a lThe Seventeenth Annual Emerging Scholarship In Women’s and Gender Studies Conference UT Austin, where gives 6 rules for allies (cross race/gender/sexuality/

nationality/religion etc). - Read this terrific blog from SMARTASSJEN about being a trans ally.

- AWEA (Auckland Workers Educational Association) is a not-for-profit organisation that supports groups and runs community education related projects. Their core aim is to promote a just and equitable society in accordance with Te Tiriti o Waitangi. They have many useful links and resources for social justice in particular the role of non-indigenous supporters of indigenous justice struggles.

-

A new book, Working as Allies: supporters of indigenous justice reflect written by Jen Margaret is now available.