When my parents were considering migrating from East Africa, their focus was on the white settler contexts of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. For a bunch of reasons I won’t go into here, they settled on Aotearoa New Zealand. A part of me always felt like my life would have been better if we’d moved to Canada or the United States, because there would have been a bigger Goan community and more support for my family. I reasoned I might have felt more culturally confident, more capable at speaking Konkani. My visit to Canada in October helped me accept the gift that my parents had given me in migrating to Aotearoa New Zealand. By not being wrapped in the comforting cocoon of an insular diasporic community, I had to figure out my own relationship with my personal and cultural history but also what Ghassan Hage terms, an ethical relationship with colonisation and living on colonised land. Visiting Canada and meeting terrific indigenous people and migrant scholars allowed me to see the contrast between Canada’s genocidal history and its self-representation as a benign, civilised and benevolent nation. The parallels between Aotearoa and Canada of a colonial history supplemented by exploited migrant labour to meet settler ends mirrored the clearly unfair outcomes in measures of health, well-being and prosperity for indigenous peoples that I see in Aotearoa New Zealand as a health professional. For the first time I began to see how the issues I’d been grappling with as a migrant were replicated across seemingly disparate white settler contexts.

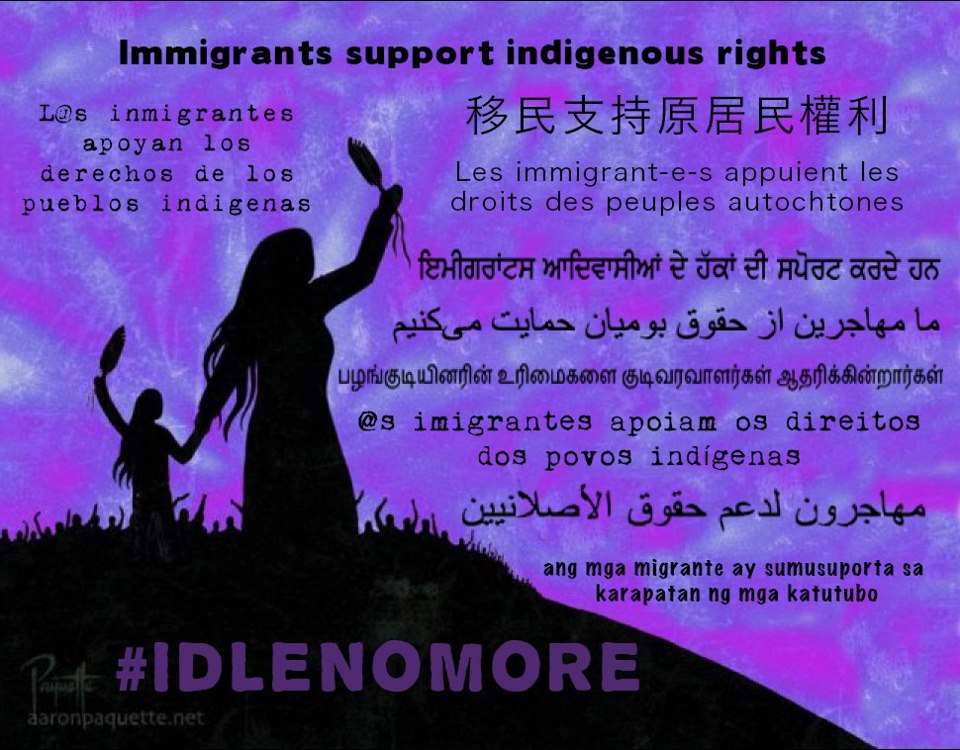

Image courtesy: Aaron Paquette

Image courtesy: Aaron Paquette

The Idle No More movement which began on Great Turtle Island on December 10, 2012 was initiated by four women Nina Wilson, Sylvia McAdam, Jessica Gordon & Sheelah McLean in response to legislation (Bill C-45) affecting First Nations people and gained momentum with the hunger strike by Attawapiskat First Nation Chief Theresa Spence. Impressively the United Church of Canada has acknowledged it’s complicity in colonization, inequality and abuse, through being one of the bodies that ran Indian Residential Schools. In 1986 they apologized to Aboriginal peoples for confusing “Western ways and culture with the depth and breadth and length and height of the gospel of Christ.” Apologizing to former residential schools students in 1998. Their response to the Idle No More movement has been to fully support Chief Spence’s statement that “Canada is violating the right of Aboriginal peoples to be self-determining and continues to ignore (their) constitutionally protected Aboriginal and treaty rights in their lands, waters, and resources.”

Other activists have also taken note of the commonalities of the struggle, noting how how what is particular, has universal relevance. Naomi Klein notes that

During this season of light and magic, something truly magical is spreading. There are round dances by the dollar stores. There are drums drowning out muzak in shopping malls. There are eagle feathers upstaging the fake Santas. The people whose land our founders stole and whose culture they tried to stamp out are rising up, hungry for justice. Canada’s roots are showing. And these roots will make us all stand stronger.

International support has come from the occupied lands of Palestine and indigenous communities around the globe. In Aotearoa New Zealand a Facebook page has been developed called Aotearoa in Support of Idle No More: Maori women’s group Te Wharepora Hou, a collective of wāhine based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland with a commitment to ensure a stronger voice for wāhine have also pledged support. As a migrant occupying a disquieting position in a country working through issues of biculturalism and mutliculturalism in a monocultural context. Diasporic migrant communities and organisations have also backed the Idle No More movement, with South Asian activists and BAYAN-Canada, an alliance of progressive Filipino organizations noting the similarities between migrant experiences and indigenous struggles.

Immigrants in Support of Indigenous Rights via Harsha Walia

Photo credit: Cameron Bode

How do we do engage with an indigenous struggle when we do and don’t belong at the same time? Himani Bannerji notes in a Canadian context (but one that readily resonates through various white settler contexts):

So if we problematize the notion of ‘Canada’ through the introjection of the idea of belonging, we are left with the paradox of belonging and non-belonging simultaneously. As a population, we non-whites and women (in particular, non-white women) are living in a specific territory. We are part of its economy, subject to its laws, and members of its civil society. Yet we are not part of its self-definition as ‘Canada’ because we are not ‘Canadians.’ We are pasted over with labels that give us identities that are extraneous to us. And these labels originate in the ideology of the nation, in the Canadian state apparatus, in the media, in the education system, and in the commonsense world of common parlance. We ourselves use them. They are familiar, naturalized names: minorities, immigrants, newcomers, refugees, aliens, illegals, people of color, multicultural communities, and so on. We are sexed into immigrant women, women of color, visible minority women, black/South Asian/Chinese women, ESL (English as a second language) speakers, and many more. The names keep proliferating, as though there were a seething reality, unmanageable and uncontainable in any one name. Concomitant with this mania for naming of ‘others’ is one for the naming of that which is ‘Canadian.’ This ‘Canadian’ core community is defined through the same process that others us. We, with our named and ascribed otherness, face an undifferentiated notion of the ‘Canadian’ as the unwavering beacon of our assimilation.

The experiences of marginalisation that Bannerji elucidates can guide our responses to the Idle No More movement. Gurpreet Singh from Vancouver, notes that South Asian seniors have always referred to the indigenous peoples as Taae Ke (family of elderly uncle). If we see a familiar connection between what we ourselves experience as migrants and extend that empathy to the struggles of indigenous people who have experienced an inter-generational slow genocide, we might be able to see beyond our own oppression and our view that we are too far outside the structures of power to claim a space. Privileged in some ways, disadvantaged in others, our futures are tightly imbricated in this indigenous struggle. Our presence has sometimes diffused indigenous claims and we must consider our complicity in the continuing colonisation of indigenous people. We must put pressure on governments to recognise the rights of indigenous people and their unique place as guardians of the lands we stand upon, our futures depend on it.

At the asset sales March in Auckland in April 2012. Banner by YAFA-Young Asian Feminists Aotearoa. Photo by Sharon Hawke.