Last week I visited the Tasman Peninsula in Tasmania, which was the country of the Pydairrerme band of the Oyster Bay tribe, before being invaded and settled by Europeans. As a a recent arrival in Australia (from New Zealand in 2013), I see it as my responsibility to develop a local nuanced understanding of settler-colonialism, the dispossession of indigenous Aboriginal people and the colonial carceral system. Port Arthur, a convict settlement for the former colony of Van Diemen’s Land on the Tasman Peninsula was on my itinerary. Maria M. Tumarkin points out that places like Port Arthur with their material remnants allow us to engage with events (like the trauma of convictism) and to experience the hardship and suffering endured by convicts without actually putting ourselves on the line. People that visit sites of trauma or traumascapes as Tumarkin calls them (also known as dark tourism (Philip Stone), thanatourism (A.V. Seaton), trauma tourism (Laurie Beth Clark) are not either “voyeuristic tourists” or “earnest pilgrims” but can also have mixed motives, some unknown to them. I wanted to better understand the colonial and convict history of my adopted homeland, especially because my partner is Australian born and has an ancestral convict history.

Port Arthur has a history of prison tourism and its sandstone, pink brick and weatherboard buildings along a beautiful cove, belie it’s disciplinary role for convicts from 1830-1877. Prior to 1840, convicts were used as colonial labour for settlers, after 1840 convicts undertook a trial period of labour in a government gang, and if this was satisfactory could then be hired out to the private sector. This partnership with the private sector transferred costs of rations, clothing and accommodation from the colonial government to private masters who did not pay wages (sound familiar?). Thus, Van Diemen’s Land was a panopticon without walls rather than a prison. More about panopticons later! For people that “abused” this “open” punishment or for whom a suitable assignment could not be found, a place of secondary punishment was needed. Hence the development of the penal station of Port Arthur to house those who could not be assigned and where labour could be extracted and the recalcitrant punished as Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart notes. After the closure of the penal station, decline and damage to the carceral buildings of Port Arthur ensued. Renewed interest in the late 1920s, saw restoration work begin so that the tourism potential of the site could be maximised. In the 1980s Port Arthur became Australia’s most famous open-air museum, and the 1996 killing of innocent people by an armed gunman did not diminish its role as a tourist site. A memorial garden now houses the Broad Arrow cafe where twenty of the thirty five victims were shot which represents a cathartic location -triggering powerful emotions.

The carceral buildings at Port Arthur including the Penitentiary and the Separate Prison in use nineteenth-century ideas about how adult deviants could be treated in order to transform them into skilled and docile members of society. Foucault used the metaphor of the panopticon designed by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham to talk about the change in society from a “culture of spectacle” (public displays of torture etc) to a “carceral culture.” where punishment and discipline became internalized. The panopticon was a prison designed so that a central observation tower could potentially view every cell and every prisoner. However, the prisoners could not view observers or guards, so prisoners could not tell if or when they were being observed. Consequently, they came to believe that they might be always being observed, and disciplined themselves into model prisoners. Port Arthur’s prison was shaped like a cross with exercise yards at each corner and prisoner wings connected to the surveillance core of the Prison from where each wing could be clearly seen, although individual cells could not (thus differing from the theory of the panopticon). Panopticism or the ever-present threat of potential or continual surveillance is a mechanism for translating technologies of disciplinary control into an individual’s everyday practices.

Reinforcing Islam and Muslims as ‘others’

This brings me to the key concern of this blog post, the events of December 15th when a single armed man took people hostage inside the Lindt Chocolate cafe in Sydney. His actions ultimately led to the death of two innocent people and overshadowed scrutiny of the mid-year budget update (which includes cuts to Foreign Aid and the Australian Human Rights Commission). The gunman had significant social and inter-personal problems but the media were quick to label the siege a terrorist attack (it was a Muslim person brandishing a flag after all) which also helped to justify future and recent past legislation limiting the movement of some groups of people. Only last week New Zealand politicians hastily passed anti-terror laws through Parliament. In the United Kingdom, PM David Cameron pointed out:

It demonstrates the challenge that we face of Islamist extremist violence all over the world. This is on the other side of the world (in Sydney) but it’s the sort of thing that could just as well happen here in the UK or in Europe.

Many media sources and other commentators were quick to jump to conclusions with The Daily Telegraph front page screaming “Death cult CBD attack” and anti Muslim scare mongering from shock jocks like Rad Hadley.

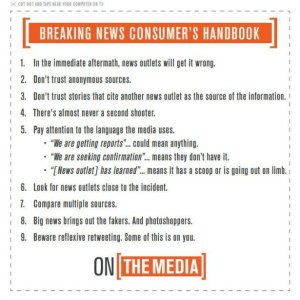

Interestingly the reportage focused on the religion of the gunman and brought out racist and inflammatory commentary from people on Twitter and Facebook. What was especially interesting was the way in which misinformation spread far and wide as Alex McKinnon carefully pointed out:

But the families of the people involved, and the broader public, have a right to information that is accurate and correct. Spreading rumours on something as potentially serious as this is not innocuous: it is actively harmful. Your best course of action is to refrain from commenting or spreading unchecked information, online or otherwise, until the facts are known, the situation is better understood and our collective emotions aren’t running so high.

In a critique of media coverage Bernard Keane of Crikey interrogated the language and phrases that proliferated in coverage:

The assumptions loaded into such “lost its innocence” statements merit entire theses; indeed, many have doubtless already been written. That Australia, established as a prison colony and forged in dispossession, genocide and gleeful participation in the long wars of imperialism throughout the 20th century, could be “innocent”; that it is such a fragile culture that a single moment of violence, however atypical, could comprehensively alter its very nature.

New Matilda predicted that there would be spike in violence against Muslims and mosques:

Just as Christian churches all over the nation were attacked in the immediate aftermath of the 1996 Port Arthur siege, Mosques around Australia will be vandalized. Because, naturally, if the siege is in fact being perpetrated by Muslim extremists, then all Muslims (and all symbols of Islam) are fair game.

Bernard Keane also predicted that media identities and journalists would:

disgrace themselves and their profession by reporting wild speculation as fact. When you’re reporting a big story on a 24 hours news cycle, and you have no idea what’s going on, you need to fill the gaps. Anything that moves is news, and if it doesn’t move, give it a push.

With the media finding:

some lone nut Muslim extremist somewhere to say something short of condemning the violence, and then portray that as the view of the broader Muslim population. Eventually, Australian media will start demanding that all Muslim leaders everywhere condemn the violence… even though Muslim leaders everywhere will have already condemned the violence.

This was an accurate prediction as in no time at all, the Australian Muslim community denounced the act:

However, Randa Abdel-Fattah problematised this gesture in the context of broader insatiable community demands:

Muslim organisations – weary, under-resourced, under pressure – were ready to condemn, to distance, to reassure because after 13 years of condemning, distancing, and reassuring, the Australian public seems to still be in doubt about Islam’s position on terrorism.

Australian responses give me hope…

As people gather to pay their respects in a very public way. I’d like to think that there’s an opportunity for healing rather than fomenting further hate and powerlessness. I agree with Tasmanian and Booker Prize winner Richard Flanagan’s observations of people:

I think evil, murder, hate… these things are as deeply buried within us as love, kindness, goodness and perhaps they are far more closely entwined than we would care to admit… And the face of evil is never the other, it’s always our face.

So with that in mind, I’d like to talk about the outpouring of grace, dignity, compassion and thoughtful analysis that I’ve also seen in abundance.

- Clover Moore Lord Mayor of Sydney:

- Victoria Rollison challenged media representations of the gunman and the framing of the siege as a Muslim issue:

“I was a teenager when the Port Arthur massacre happened, and I don’t recall there being a backlash at the time against white people with blonde hair. I’m a white person with blonde hair, and no one has ever heaped me into the ‘possibly a mass murderer’ bucket along with Martin Bryant. Or more recently, Norwegian Anders Breivik, who apparently killed 69 young political activists because he didn’t like their party’s immigration stance which he saw as too open to Islamic immigrants. In fact, in neither case do I recall the word ‘terrorist’ even being used to describe the mass murders of innocent people.”

- Clementine Ford similarly pointed out that Christianity has not come under the same scrutiny in other violent incidents, both in Australia and Norway, while also addressing the issue of violence against women:

Almost without fail, non-Muslim white men who behave as he did are given the benefit of individual autonomy. When Rodney Clavell staged a 13 hour siege at an Adelaide brothel in June of this year, his reported Christianity barely made any of the news reports. Where it did, it was in articles which spent a good proportion of time talking about how much of a good bloke he was. Norway’s Andres Breivik – a right wing Christian who murdered 77 people in 2011 – was frequently described as ‘a lone wolf’. His actions were certainly not treated as a defining characteristic of members of the Christian faith, nor did Christians have to fear backlash once his affiliation was revealed.

- Max Fisher responded:

This expectation we place on Muslims, to be absolutely clear, is Islamophobic and bigoted. The denunciation is a form of apology: an apology for Islam and for Muslims. The implication is that every Muslim is under suspicion of being sympathetic to terrorism unless he or she explicitly says otherwise. The implication is also that any crime committed by a Muslim is the responsibility of all Muslims simply by virtue of their shared religion. This sort of thinking — blaming an entire group for the actions of a few individuals, assuming the worst about a person just because of their identity — is the very definition of bigotry.

- The hashtag #illridewithyou (but also note Beyondblue’s national anti-discrimination campaign in 2014 which highlights the impact of discrimination on the social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal people which has not had the same flurry of support). Also some interesting critique from Eugenia Flynn who asks What happens when the ride Is over?

- Interfaith action from mosques, synagogues and churches inviting the public to gather for unity, and against violence, fear and hatred.

- Social media sharing guidelines from Alex McKinnon:

When in doubt, wait. When you are not in full possession of the facts, remain silent so that more informed voices can be heard

- Good to see some thought about the people who survived the siege and their recovery.

- Lastly, it’s great to see some critique of mass media practice from John Birmingham in the Canberra Times and Bernard Keane in Crikey.

Ending with a reflection

Thinking with sadness of all the people traumatized by yesterday’s events, the innocent people that lost their lives and all their loved ones in Sydney. Thinking also of people who live with and are caught up in acts of power, control and violence which are not of their own making globally. Thinking of the ways in which ‘our’ institutions serve ‘us’ and how responsibly they exercise their power and influence (police, media, politicians), whether their role creates calm, understanding, light or heat, marginalising and stereotyping. Whether the creation of an ‘other’ is necessary and what future it holds open for ‘others’ who experience heightened vigilance, policing and surveillance. Thinking of those who work for peace, who work to address injustice. Thinking of the need to not conclude too quickly, to not judge too harshly before understanding. Mostly today sending love, prayers and hope into the world in this season of peace and goodwill.