This is a longer version of a foreword in the Winter 2016 edition of the Hive (the Australian College of Nursing’s quarterly publication). After the refs, I’ve added my own experience of living through Cyclone Isaac, which was declared by the Tongan authorities to have been the worst disaster in Tongan history. You can also download the pdf of Receiving the stranger.

If one agrees that the manner in which a society receives refugees (the stranger) and upholds their rights is a fairly accurate barometer of the extent to which human rights are generally respected, it follows that an investment in promoting the rights of refugees is a an investment in a more just society for all (Harrell-Bond, 2002, p.80).

This special issue on disaster health acknowledges the relational aspects of being a human. A disaster is the widespread disruption and damage to a community that exceeds its ability to cope and overwhelms its resources (Mayner & Arbon, 2015, p.24). At times of disaster, people need help, and nurses are often on the front line. This is because even outside of what we usually understand to be a disaster, nurses typically work with people and communities who have exhausted their own resources or who need infrastructural and systemic support to galvanise their resources and strength.

The call to care that we associate with nursing practice is often juxtaposed with an uncaring social and political context. This leads many nurses to experience moral distress, defined by Jameton (1984) as “aris(ing) when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action”. The lack of care in our border discourse reflects how devoid of context the issue of migration is in political debates. Fleeing bodies are objectified and dehumanised by politicians who trumpet xenophobic and alarmist discourses of fear. These discourses are oriented toward a mass media for distribution to people as a proxy for actual engagement with refugees and asylum seekers, underpinning cruel deterrence policies and for-profit detention of vulnerable people. For the practitioner, even if one is concerned, the dominant economic order of neoliberalism keeps us focussed on outputs rather than relationships, we keep our heads down to keep up. Our working situations often pull up the drawbridges to our hearts and selves so we can survive.

The work of the three refugee health nurses and an arts practitioner working for refugee support organisation RISE provides important lessons for us, even if we do not work directly with former refugees. The profiles emphasise the relational aspects of nursing: skilled, empathetic, compassionate care that is tailored, solution-oriented, flexible and seen as safe by the recipient. Care which is delivered by providers who are skilled communicators who use interpreters as needed: cultural competence is not about being of a particular culture but of knowing how to bring resources to a new cultural situation where one has limited expertise. The practitioners profiled here continuously attempt to improve through evaluation and overcome resource constraints to work toward models of care that facilitate shared decision-making. And outside the clinical relationship, these practitioners articulate and demand strategic interventions to disrupt institutionalised discourses and practices that have a marginalising effect on vulnerable communities.

Paradoxically, this move from individual to collective and community responsibility – demanding in an individualist culture – can resource our weary hearts, minds and bodies. The critical perspectives foregrounded here draw on new understandings of intersectionality as a key issue in addressing health inequity. They show how categories of difference such as race, gender and class intersect with broader social, economic, historical and political structures to shape experiences of health care. They allow us to look “upstream” (Clark et al, 2015) and to critically evaluate the virulent anti-asylum seeker rhetoric made by politicians and media that refugees and asylum seekers are “trying to take over”, are not “genuine”, are not using the “proper channels”. They surface the often overlooked truth that the Geneva Convention — to which Australia is a signatory — provides people in fear of their lives with a legitimate and legal right to seek asylum. Intersectionality might allow us to engage in cultural safety, to see how our ‘selves’ intersect with the institutional, geopolitical and material aspects of our roles; to consider the investments and conditions that enable us to care and to interrogate the constraints and accountabilities that influence our practice.

Much of the history of critical nursing practice has focused on the “reflective practitioner” (Schön, 1983). However, in the real world there’s rarely time to reflect and institutional demands often preclude reflective time. And reflecting by ourselves assumes we can be fully aware or conscious of ourselves and the social relations that we are a part of. This kind of deliberation cannot adequately address the messy unpredictable nature of nursing contexts.

We might need to start talking to each other again, working in partnership to take part in more socially engaged knowledge practices, where we recognise the limitations of our own knowledge so we are better able to work across difference. Nurses are already skilled at building relationships with clients. We need to extend our therapeutic alliances to families, communities, service providers and community resources. The ACN and nursing’s other professional organisations have taken up the challenge, speaking out against Australian policies and practices that impact on the health outcomes of detainees, asylum seekers and refugees — the secrecy provisions of the Australian Border Force Act of 2015 being a key example. What are our collective responsibilities now? As they have always been: to conduct ourselves with a duty of care. However, in this increasingly complex world, effective care is no longer a matter of caring only for the individual, but requires partnerships that transcend the boundaries of clinical practice, research, education, and political advocacy to work more collaboratively and improve the well being of those marginalised by our nation’s unhealthy policies.

References

Clark, N., Handlovsky, I., & Sinclair, D. (2015). Using Reflexivity to Achieve Transdisciplinarity in Nursing and Social Work (Chapter 9). In L. Greaves, N. Poole, and E. Boyle (Eds.). Transforming Addiction: Gender, Trauma, Transdisciplinarity (pp.120-136). London: Routledge.

Harrell-Bond, B. E (2002). Can Humanitarian Work With Refugees Be Humane? Human Rights Quarterly 24(1):51-85.

Jameton, A. 1984. Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Schön, D. A. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: how professionals think in action London: Temple Smith.

My own experience of disaster: Cyclone Isaac 1982

The Kingdom of Tonga is made up of 170 islands, of which 36 are inhabited. Two-thirds of the population live on Tongatapu the main island. Cyclones occur once every 1.6 years on average.

Cyclone warnings were broadcasted frequently when I went to Tonga High School in 1982. The morning of March 3rd was no different, but this time we didn’t go to school. It was overcast and the wind had picked up. We had a lush tropical garden lovingly tended by my parents with sporadic assistance from their three daughters. The first thing we noticed which was kind of funny, is that it started raining pawpaws, then breadfruit and bananas which I found hilarious. Then it got less funny, banana trees started doubling over, branches started flying past, then sheets of corrugated iron, all the while it was raining hard. We had the sea in front of us and a lagoon behind us, we wondered what it would end. Our electricity supply disappeared and then our neighbours joined us as they were worried about flooding.

Cyclone Isaac was declared by the Tongan authorities to have been the worst disaster in Tongan history, because of the magnitude of the destruction of housing, public buildings and livestock (up to 95% in some

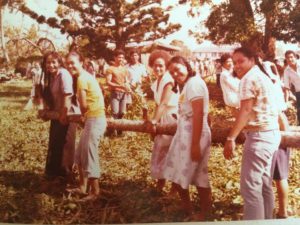

places). According to this shelter case study on disaster mitigation public buildings were designed using seismic and cyclone codes from Australia and New Zealand, but these were not applied to private housing, so some house were built with poorly secured metal roofing sheets (explaining why sheets of corrugated iron had been flying past). What I remember most about that time, was how quickly we all mobilised collectively to clean up the mess and also how quickly international aid arrived.